Having lost his traveling performer father when he was young and rebelled against his strict mother, Kazuya Yoshii was raised by his grandmother. This story of his has been told many times before. Not only did it make for a dramatic upbringing, but it’s greatly influenced Yoshii as a lyricist. The Yellow Monkey’s new album “Sicks” contains the third in a trilogy of songs about Yoshii’s actual family, “Jinsei no Owari (For Grandmother)”. The other two songs are “Silk Scarf ni Boushi no Madam” (where he sung about his mother) and “Father” (where he sung about his father).

The tracks he follows in “Jinsei no Owari (For Grandmother)” is the next step up for Yoshii as a lyricist, and it’s no coincidence that the masterpiece album that is “Sicks” contains the final song in this trilogy. Yoshii is now able to stand on stage as a brand new lyricist, free of these themes of family and upbringing. In this feature we’ll take a look at ten songs that represent his work, centered around the songs in this trilogy. We’d also like to use this interview to examine why “Sicks” gave birth to so many wonderful songs. It should be treated as a document that far surpasses any simple tracing of the band’s history through their hits.

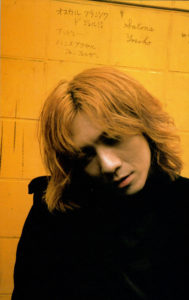

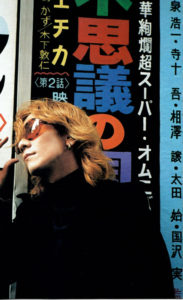

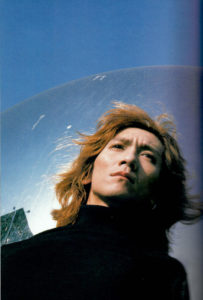

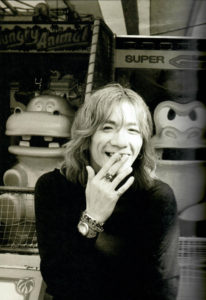

Interview & Photography: Youichi Shibuya

(From Bridge Vol. 14, April 1997)

1. Welcome To My Doghouse

I’d like to begin with your indie album “Bunched Birth”.

(Yoshii) Sure.

I selected “Welcome To My Doghouse”, even though I wish I could ask about pretty much all the songs from this album. Just what kind of mood were you in when you wrote this song?

(Yoshii) When I was recording this, I felt very much like I was…I use this expression often, but a big fish in a small pond. We were still playing in clubs so it’s not like I felt like we were conquering the world or anything, but that’s how it was at the time. The other members of the band would talk about this quite some time later, but this was a point where we were worried about what it was we were going to make. But we’d recorded a demo tape before that, and through that I could see that this was going to be a good album. It ended up being really well done, and I felt like we had nothing to fear since we were debuting with something of that quality. I was kind of full of myself at that point, as you can see.

But I kind of feel like your first major label album was way more distorted feeling than this one.

(Yoshii) Yeah.

So that’s why this one feels so much more mysterious. It has an amazing energy to it, and I think it’s just all around a great album.

(Yoshii) I agree.

To put it a different way, you’ve only just ended up returning back to this point after so long. Sorry to phrase it that way, I was just very surprised when I heard this album. I kept wondering why you didn’t do more of this! (Laughs)

(Yoshii) No, I get what you mean. Whenever we put out a new album I always listen to it and compare it to “Bunched Birth”. I did that for both “Smile” and “Jaguar”, pretty much whatever we put out.

Wow.

(Yoshii) Even putting aside how complete of an album it was, it just feels very chic, right? I always feel like I’ll never be able to surpass that. When I’m writing songs for new albums I always feel like I do, but then change my mind about that some time after the fact. I think that’s very indicative of me and my mental state.

What qualities make you think this is such a well made album?

(Yoshii) Because I wasn’t nervous about it at all.

Ahh, so that’s what it was after all.

(Yoshii) Yeah. And everyone who knew me back then says this, but I wasn’t a very pleasant guy to be around at all. I was at least 1000 times worse than I am now. Even down to my expression…it wasn’t threatening, more just bad and dangerous.

Would you say the time at which you made this album was the point at which your life was the most crazy?

(Yoshii) Yeah, that would have been around the time of “Bunched Birth”.

Wow. So you were involved with a bunch of different women.

(Yoshii) A bunch.

So you were being pretty immoral in terms of that.

(Yoshii) That’s right.

(Laughs) Typically at this point you can’t really earn a living from being in a band.

(Yoshii) I wasn’t able to at all then.

So you were using those women in order to help support yourself financially. Did you feel guilty about that at all?

(Yoshii) Not at all. The women involved were enjoying it too, and it’s not like I was forcing any of them…mostly (Laughs)

(Laughs)

(Yoshii) No, but I had a lot of debt too. Even though thinking about it now, it wasn’t all that much! (Laughs) It was from buying instruments when I was starting up The Yellow Monkey. I was still playing bass at that time, so I took out a loan, ordered a new bass, and practiced everyday. And just when I started getting into the swing of it, I heard that Heesey had quit the band he was in. I told him “Hold on!” (Laughs) “You should play bass! I’ll just sell this and buy a guitar amp”. So I went out and bought an actual guitar too, which just increased the amount of debt I was in since I took out a loan with Marui department store for that (Laughs) Then I got fired from jobs and lost most of my income. I didn’t like working in factories and stuff as a day job, because I worked in the entertainment business after all. So given that, I didn’t necessarily work all that much in any given month. I had to pay back 80,000 yen per month and I was only making about 30,000. So about all I could do was rely on women to help me out.

(Laughs) That’s hard to relate to!

(Yoshii) That’s fine, it was hedonism anyway.

So what was your style of song writing like back then? Did it feel like you were just going for it in a straightforward way?

(Yoshii) No, I was really kind of massaging the lyrics, since I had the time and everything.

Ahh, I see. They have a relatively high amount of energy to them, so I was wondering if you were just kind of going for it when writing them to achieve that.

(Yoshii) No, those were songs that we’d done a ton of times live before recording them.

Okay, so they were already really established.

(Yoshii) That’s why it was just kind of like “Okay, I guess we’re recording “Jaguar” now!”. We were really great at arranging those songs back then, and I wrote a ton of them.

So once you established your motif, you’d keep on revising it over and over.

(Yoshii) Yeah, it hadn’t been very long at that point since I’d even started writing songs. I didn’t really know anything about the process of composing at all. I still don’t know much about it from a theory perspective, though that’s probably weird to say. I do it mostly by feel, and I think there was quite a bit of beginner’s luck involved too. It’s a gift of mine.

I’d say it’s a talent.

(Yoshii) More like a series of flukes.

Flukes tend not to come in series, so I think it’s talent. Since you don’t want to say it, I will: It’s really amazing. I felt this really was a maiden work that had everything.

(Yoshii) Yeah. I really do love it, and I used to listen to it everyday.

So to return back to something like this when making albums means that this is a touchstone for you.

(Yoshii) Yeah. As I’ve gotten older I’ve started thinking of that feeling of inexperience as being very nostalgic, and I’ve yearned for some of those aspects of my younger self. I’d listen to him doing some sort of a comedy skit and say something like “I’ll tell you this: You’re still a young idiot, but you’ve got energy!” (Laughs) That’s really sad, isn’t it?

(Laughs) How do the other band members feel?

(Yoshii) I haven’t asked them about it directly, but I suspect they’re very aware that it was our starting point. I think it’s probably an album that they still like quite a bit now too.

What a great starting point.

(Yoshii) It is, isn’t it?

There are people who want to lock their debut albums away or erase them from existence, but this isn’t one of those at all.

(Yoshii) Yeah. So that’s why when writing albums since getting signed, somewhere in my heart I’m thinking about how I can’t surpass “Bunched Birth”. But I’m very grateful for that.

So what were your concerts like during this era?

(Yoshii) Ha ha, our concerts from this era? They were…if I were going to see The Yellow Monkey from back then playing at a club as myself today, I’d probably think “Oh god, these stupid kids!”. We never really said anything bad, but we were very brazen.

Wow.

(Yoshii) And the audiences for our performances were full of people that looked like they could be on their way to the strip club (Laughs) We were playing for older woman who seemed like they’d be saying “These guys aren’t getting signed. It would be better if they were a lot shadier looking”.

(Laughs) Seriously?

(Yoshii) Seriously! I was 23 or 24 at the time, and these women were probably 30. So they really felt like they were from a strip club to me. They’d say “We’ll buy tickets for your next show” in a very specific way.

It’s not like they sat next to you and kept you company or something though.

(Yoshii) Hey, Takako Inoue (an All Japan Women’s pro wrestler) came to see us play at the time, and said that we were like Kome Kome Club!

Oh wow.

(Yoshii) “A provocative version of Kome Kome Club”. And Kome Kome Club was already pretty provocative, so that really meant something! (Laughs)

It’s pretty cool that you were considered provocative. What did you think about that? They’re coming to see your band instead of going to the host club.

(Yoshii) No, I really went for women who are basically widows without ever having been married…

Widows without ever having been married! (Laughs)

(Yoshii) This will probably get some people mad at me again! (Laughs) But I really like that type of woman. It’s a weird way to put it, but they’ve just got a certain thing in their hearts. It doesn’t mean they’ll never get married, but it was just a very fun quality to have around when playing in a rock band. Yeah.

You were definitely the only ones in Japan that had that kind of aesthetic sense or values.

(Yoshii) You really think so?

I definitely do. There weren’t any other bands saying that it was fun to be around women who have darkness in their hearts and won’t get married.

(Yoshii) And around 30 is the age where women tend to go see fortune tellers a lot in groups. They just give others names by saying like “That girl, she’s Pandora’s Box”. And they’ll say “And you are too!” (Laughs) That kind of stuff is a lot of fun, in its own way. But it’s even more fun that some of them are still coming to our concerts.

Like they’re saying “Oh, those boys are all grown up!”

(Yoshii) Yeah, yeah. That’s what it feels like.

It’s almost like that awakened protective feelings within you, instead of feelings of attraction. You were probably taking the stance that if you weren’t more protective then everything might just break apart.

(Yoshii) Yeah, you’re probably onto something there.

Did you enjoy your life quite a bit back then?

(Yoshii) Yeah. I was in the prime of my youth, after all. It’s weird for me to say it myself, but I’m not that kind of a person by nature. I had a lot of honesty and morals instilled in me, so I didn’t really start living my life that way until I was around 20. That was probably my reaction over the course of five years, from 20 to 25.

You wanted to lean toward your bad side with everything you had. You weren’t forcing yourself, but you were at a point where you felt like you’d been freed from something and you’d discovered your true self.

(Yoshii) Yeah. It’s like I was saying “I didn’t realize anything in this world felt so good!”. That’s what it feels like.

At any rate, seems like you were quite popular with the ladies.

(Yoshii) Yes, yes. It’s like going to Ryuuguujou and getting completely cleared out (Laughs)

(Laughs) Wow, that’s amazing. Mr. Oomori (the president of the group’s management company), it seems like the group attracted middle-aged women back then.

(Oomori) Well the group are all around 30 right now, and it’s not like they stopped attracting them after they debuted. That’s why Mr. Munekiyo (the group’s directory when they were on the Columbia label) always said “We have to target female high school students!”.

(Yoshii) Yeah, yeah. He said “We have to lower the age of our target market to female high school students!” at a marketing meeting or something, and I remember reacting by saying “You’ve got to be kidding!”. That’s the kind of environment we were working in. But you know, we take surveys at our concerts still. But the ones we gave out during the “Bunched Birth” era had some different questions on them. There was one for “Which band member do you want to have sex with?”

(Laughs)

(Yoshii) (Laughs) And everyone actually filled it out too! I’d go through them and be like “Ah shit, this one answered Emma!”. Horrible, right?

(Laughs) About how many copies did your indie album sell?

(Yoshii) Back then? Do you know how many?

(Oomori) 1000 copies.

And how many copies did the later reissue sell?

(Oomori) 100,000 copies.

When it later sold that many copies, how did it feel? Like you were getting revenge?

(Yoshii) Nothing like that at all. I’d often look at the ranking charts like Oricon with the other band members. I remember noticing it and saying “Oh wow, “Bunched Birth” sold this much huh?” and laughing about it (Laughs)

2. Romantist Taste

So what happened between then and when you got signed to a major record label and released “The Night Snails And Plastic Boogie”?

(Yoshii) Basically our booking manager at La.mama at the time started giving presentations to different record companies after we made “Bunched Birth”. And they said we’d be signed within the year. We’d just started headlining shows, so we were kind of wondering if this was all going to be okay. There were two record companies that were interested in us, so it came down to figuring out which one to choose.

Was it a relatively smooth transition then?

(Yoshii) Yeah. It was smooth but…I was anxious about it. Mentally anyway, since I don’t think there were any issues musically speaking. I learned a lot between when we released “Bunched Birth” and when we started making our first album on the new label. About relationships between musicians, doing this results in that, etc. There were a lot of things I grew to lust after and want to do.

But whereas “Bunched Birth” was a relatively straight-forward rock album, the next album would change into something more complex. Just why was that the case? It’s always been a mystery to me. Was it a natural transition for you? An extension?

(Yoshii) It was supposed to be an extension, but it didn’t really end up being one at all! (Laughs) Though I was really pleased with the recording quality of “Bunched Birth”, I thought that the recording for a major label album should be of a higher one. So there were all these things I really wanted to try: Adding in strings, more female choruses, and having a bunch of channels. Come to think of it, the channels may have been the problem. I’ll put the blame there!

I don’t think that’s what the problem was.

(Yoshii) …But I was really worried during the recording process. I couldn’t figure out why it it felt so different.

Why what felt so different?

(Yoshii) The sound. Why is it so hard for me to sing this? Why isn’t the sound I want coming out? That sort of stuff.

You were in a much fancier studio, after all.

(Yoshii) Right, right. We had a lot of cutting edge stuff there, instruments and all that. Between that and the pressure gradually building up, it didn’t put me in a very good head space. I kept thinking “This is weird, why can’t we get this kind of sound on a recording? We did it before…”. I was pretty inexperienced, so I couldn’t really consult with anyone on it. I’m not sure if it was so much that I couldn’t as it was I just kept saying “I wonder why this isn’t working”. That was a part of it too.

So you were really happy to finally be on a label, but at the same time you were kind of spinning your wheels.

(Yoshii) I was.

Huh. So how did you manage to get over that?

(Yoshii) Well…if I’m being honest, I didn’t really get over it until “Smile” was done.

That’s really a long time! (Laughs)

(Yoshii) Yeah. And the thing I really thought was dumb after the fact was how was thinking that I was so pop art the entire time.

Ahh, I see. That’s understandable though.

(Yoshii) Yeah. So…today for example we did photoshoots in the subway and in front of the cherry blossom trees for this article. Being in those kind of situations doesn’t suit me at all, and I felt like I was a completely different person. I used to think that if I got rich, I’d be some kind of refined pop art guy wearing linen all the time, living in like a retro future. And over time I gradually came to realize that just wasn’t me. At the time I wanted to have a very natural type of sound, but nowadays we have kind of a more mainstream one by comparison. That’s what I wanted at the time, anyway. I was really worried about why I couldn’t manage to get the clear pop sound that I was looking for.

Wasn’t “Night Snails” a title that you came up with?

(Yoshii) Yeah, yeah, yeah.

In what way does that title suggest pop?

(Yoshii) (Laughs) No, no. You see…

It’s such a messy title. It needs to put compressed down quite a bit!

(Yoshii) (Laughs) You see that’s where I’m a bit of an idiot.

So you didn’t think it needed to be compressed down?

(Yoshii) No, because it was more refined than that. It was Shibuya-kei before there was Shibuya-kei. That kind of music was gradually starting to stand out more from around the time of our second album. Shibuya-kei and other sorts of fashionable styles of music. And all I could do was think “But we were already kind of doing this!” (Laughs)

You’re kidding! (Laughs)

(Yoshii) No I’m serious! (Laughs) I’m really serious…but you’re looking at me with a lot of pity right now…(Laughs)

No! (Laughs) I was just thinking that people don’t necessarily know themselves.

(Yoshii) Yeah. I really wanted to put my heart into doing a lot of sampling and such. And have us all wearing orange or blue clothes. So although I was finally able to do this for “Smile”, all sorts of friends and people around me said “This isn’t who you are”. “This isn’t the part of you that’s appealing, right? Of course The Yellow Monkey’s appeal will come out like this, but that same thing won’t happen for you”. And I started wondering if that was actually true! (Laughs)

It made you realize that for the first time.

(Yoshii) Yeah.

Were you even thinking you were a pop guy as you were making “Jaguar”?

(Yoshii) “Jaguar” is what finally settled it for me. I kept thinking “This isn’t how I wanted this to turn out”. Even though I wanted to do something that was like more strange, with us wearing gaudy camo prints, I wondered why it ended up turning out the way it did. I wondered why it turned out like something that belonged the Chiyoda Ward instead! (Laughs)

(Laughs) It’s like you were thinking “But I was going for Mintao Ward!”

(Yoshii) Yeah, exactly!

Like “I want it to be Minato Ward, or at the very least Shibuya Ward!”

(Yoshii) Right. I wanted the music video for “Kanashiki Asian Boy” to have more fluorescent colors in it, and then wondered why it ended up with so much dark red in it! (Laughs)

But that was something you came up with all on your own.

(Yoshii) It’s true that there are elements of Yukio Mishima and Akihiro Miwa hidden in me, I like that sort of unrefined stuff. But so many people go over to pop from that, right? Within a reasonable range anyway. But that kind of came to the fore for me too. When I shaved my head for “Jaguar Hard Pain”, the image of Jaguar that I was going for was really very pop. But anyway, it was very unrefined too! (Laughs)

That’s really interesting. So then at the point in time when you were writing that first album, it feels like you were a bit lost and sort of going through some trial and error.

(Yoshii) Of course I was satisfied with it when it was done, but I think it was only an amount of satisfaction appropriate to the level we were at back then. And then I made a pretty big mistake: I left the sound mixing to Shuji Yamaguchi (the sound engineer for the album), and what he gave me was something that sounded incredibly cool and powerful. And then I told him it wouldn’t work, so he did redid it in a very dejected way.

Ahh, I see.

(Yoshii) Listening to it now, I think “Foxy Blue Love” sounded the coolest of all, it’s the one song I’ll never be able to forget. It had a real machinegun-like intro and I said it was no good.

It’s no wonder anyone was able to interpret what you wanted at all.

(Yoshii) (Laughs) And even if they’d done everything, I probably would have still said it was wrong. But I really don’t have any regrets about any of it.

Are you sure you’re not just making yourself say you have no regrets about it?

(Yoshii) …Maybe just a bit (Laughs)

(Laughs)

(Yoshii) I guess I do after all. Nirvana released their first album around that same time too.

Oh yeah, that’s right.

(Yoshii) Shuji bought a copy and brought it back to the studio, as I recall. I thought the way it sounded was really amazing. And then during a meeting, I played a Pink Lady CD for him and told him I wanted the strings to sound like that. He used to work on Pink Lady tracks earlier on his career, so he just put his head in his hands! (Laughs)

(Laughs) So having fundamentally complex lyrics and very difficult to understand and decadent costumes were the perfect things for you at the time given the era, right? Even though I keep asking about this over and over again…

(Yoshii) Yeah.

To phrase it differently, would you say that without those things, you couldn’t have made it?

(Yoshii) I guess I would.

So you thought of that as a given at the time, but it really did end up being true?

(Yoshii) It was mainly us imitating glam rock fashion…well at least the glam rock fashion that we like from the 70s. Since our indie days, we were very picky about the shape of our pants and collars, for example. But those kinds of clothes weren’t really sold anywhere. Now you can find them all over the place, I mean even people imitating Namie Amuro’s fashion wear those same kinds of boots. You didn’t used to be able to buy them at regular shoe stores, you had to special order them in Yotsuya and they’d make them for you. In one way or another, we had the desire to get our costumes just so, and play glam rock. We had a great costume designer that we knew from before we debuted, so we thought everything was going to be perfect. We’d put in an order for these costumes, in this style…and then they’d just arrive! (Laughs) Of course back then we’d get laughed at and people would say “That’s one hell of a look!”. But I don’t think we hear that so much anymore.

Right.

(Yoshii) Yeah. So that’s why we aren’t really all that remarkable. And I’m glad for that.

But you thought of yourselves as being Shibuya-kei, in hindsight. Is that why you looked the way you did? Was that your idea of fresh fashion? It didn’t really come through at all.

(Yoshii) You’re right, it didn’t.

It was glam rock style no matter how you think about it. You even just said that you wanted to play glam rock, right?

(Yoshii) Yeah it was glam, but it was a more refined than that.

I’m not really sure where that bias comes from. What do you mean by refined glam rock, exactly? I understand what you mean by refinement, but there really isn’t any such thing as watered down glam rock. Glam is glam, right? Isn’t that how it is?

(Yoshii) Yeah. But for example, Iggy Pop was pretty raw sounding back when he released “Lust For Life”, right? But nowadays with that song featured in the movie Transpotting and all, it seems pretty pop sounding, right? That’s what I mean.

Ahh, I see.

(Yoshii) That’s the feeling I mean! Picture Iggy Pop in a room with Japanese furniture, that’s what I mean.

I see, mentioning Trainspotting somehow helped me get your point. You were ahead of your time.

(Yoshii) That’s a great way of putting it! Yeah. But we were all messed up because we had no skill in doing this kind of thing yet, and no producer.

I see. But as you said earlier, you fundamentally were not that kind of person, you just wanted to do those kinds of things.

(Yoshii) That’s right.

You were sort of a destructive person.

(Yoshii) I guess some other artist ended up with all the things I didn’t have.

Basically it was like you were wondering why when you showed your true self, you were being misunderstood.

(Yoshii) Yeah. “Even though I’m trying to be more refined, why am I sticking my face in honey!? I’m burying my face in jelly here!” (Laughs)

3. Avant-Garde de Ikou yo

Next we have “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo” from the second album (“Experience Movie”). This is song that you all continue to perform regularly, even now. Does that mean that you have some affection for it?

(Yoshii) “Romantist Taste” was a song that I wrote back in our indie days, so I didn’t really think of it as a single. I wasn’t aware the record companies just went ahead and took songs from an album, and cut them into singles. They probably didn’t do it because they thought it might sell, but I remember them saying something about it maybe getting used in a Camelia Diamond commercial or something. But thinking about it now, there’s no way that would have happened! (Laughs) So “Romantist Taste” ended up being no good, it didn’t sell as a single. Of course that was because your average person couldn’t just listen to it and understand what the lyrics meant, as I was told. Our director at the time told us we needed to put out a single that would sell a bit better. Of course I agreed with that, so I got to work on one. And even though what I made is now what I’d think of as a glam pop song, I think I was betting everything on that style. Especially when it came to releasing singles. I wrote them with the idea of them being used in cosmetics commercials. And that continued even into “Kanashiki Asian Boy” (the next single), with lyrics like “cherry blossom colored lips” and “The lips of a woman in love”. I guess I was thinking we could get them in a lipstick commercial! (Laughs)

(Laughs) What an amazingly immature tactic.

(Yoshii) (Laughs) No, but I seriously was thinking that way. My composition style back then involved taking different compositional elements that I liked and making them cohesive, and that was a hit song.

I see. So you put a little “Ziggy Stardust” in there, some Sweet sounding elements there, some Sparks here…

(Yoshii) It was an era where I’d be happy just by mixing in some elements from the theme song to the drama “Arigatou” or some Finger 5. So when I finished writing “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo” at home, I thought it was going to be a mega-seller. I thought it would compete against “Oyoge! Taiyaki kun”.

Seriously?

(Yoshii) (Laughs) Seriously. Maybe “Oyoge! Taiyaki kun” was overdoing it a bit. I was thinking it was going to take the industry by storm though.

I see. What was your basis for thinking that? Was it the different elements you’d put into the song?

(Yoshii) No, but it was a pop song, and we hadn’t had a song as good as “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo”.

I’m just wondering why you thought it would compete against “Oyoge! Taiyaki kun” with a title like that.

(Yoshii) I don’t know, you never know how things are going to go.

You say that, but the title “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo” is totally an indies title!

(Yoshii) It may have been a bit irresponsible. I often said stuff like “I don’t know, but it’s avant-garde” when asked what kind of song it was during our promotions! (Laughs)

So “Night Snails” was written through trial and error, but did it feel like this next album was going to show some appeal in terms of sales? Or were the exepctations rather low given how well “Romantist Taste” did as a single?

(Yoshii) I never thought “Romantist Taste” would sell much of anything anyway. I thought the album would, but the single didn’t get much notice at all. But I did think that “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo” would sell. I knew that we had to try to capture more of the straightforward feeling of “Bunched Birth” with this album. The last album wasn’t that popular, so I developed a bit of an inferiority complex. But there was also still some of that “I’ll do what I want!” energy in it too.

But it still has a sort of theatrical quality and some kind of story with costumes to go along with it. So your style of needing to borrow those fictitious elements didn’t change.

(Yoshii) It didn’t.

And I’m not sure how you consider that album to be straightforward.

(Yoshii) After each album we released, I weirdly started feeling like it had to make news.

What do you mean by “news”?

(Yoshii) Well the fact that I had a snail on me on the cover of the first one was mentioned.

It was a topic for the media.

(Yoshii) Right, right. I was thinking that they’d say something like “He’s wearing women’s clothes on the cover of the next one”, even though no one did! (Laughs) It was a bit of a topic in my neighborhood though: “I guess he’s going to be wearing women’s clothes this time!” The reason I did that was…what was it…I guess it was just because I wanted to.

Whether it’s you with a snail, women’s clothes, or even being Jaguar the next time…you could see your desire to want to motivate and agitate others.

(Yoshii) Yeah, that’s true.

So you were always putting yourself in relatively risky positions, and pulling others into them with you.

(Yoshii) Yeah, that’s also true! (Laughs) It really is.

That’s how it feels anyway, somehow. You used the phrase “news”, but I’d call it sensationalism. In a way that’s a very important aspect of rock, and you’re making it something of a theme.

(Yoshii) That’s true.

And it was done in a very clumsy way…

(Yoshii) (Laughs)

Back then you were never really conveying all of this to others, you were just coming off as weird.

(Yoshii) Yeah. If I did it now, it would probably come out differently.

If you were to dress in women’s clothes now, you’d get what you were hoping to get out of this second album.

(Yoshii) You think so?

So why do you guys love this song so much? It’s not like it was a big hit for you. There must be something to it, something that makes it “yours”.

(Yoshii) Yeah. Whenever we do “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo” during a concert, the feeling that we have as a band is very close to one in particular that I really love.

What do you mean, one that you really love?

(Yoshii) How should I put it…it feels like we’re young again?

Ahh. In that case, any song from this album should do the trick, right? If not, what’s so special about “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo”?

(Yoshii) I’m not really sure why myself. Maybe just because…it makes us happy when we play this. It’s like we all think about what a good time this was for us.

It creates a unique atmosphere between all of you.

(Yoshii) Yeah, yeah.

Wow.

(Yoshii) So it might be sort of an irresponsible song, but when I sing “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo Baby!” it just feels so right! (Laughs) I’ve been talking about this during concerts lately! (Laughs) “I’m not sure what we’re trying to say here, but it sure is fun.” It’s a song that can really work live, as like a finale or something. Yeah. That’s why we never do it at the beginning or middle of a concert.

That’s true.

(Yoshii) Like The Drifters and that song that goes “Baban-Baban-Baban”! (Laughs)

Or “minna sama~” at a takarazuka show.

(Yoshii) Right, right!

Or “shan-shan-shan” on “Arigatou”.

(Yoshii) That’s exactly the feeling I mean.

So there’s not much there in terms of concept, but it seems like it’s still an important song. I was saying that your latest single “Love Love Show” feels a lot like this one, do you think that’s the case?

(Yoshii) Well, “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo” is a song that makes the band really happy. I’m sure the audience has fun with it too, but we’re not really sharing the same happiness.

Gotcha, gotcha.

(Yoshii) “Love Love Show” is more of a song for everyone, not just us.

I see, it’s a song you can all share.

(Yoshii) Yeah. It has more of a welcoming feeling to it.

You put it very aptly just now. For someone like me who’s listening to and learning about Yemon after the fact, your impression of songs like these is that they’re just frivilous. But you’re saying that they’re good songs for those times because they’re frivilous?

(Yoshii) Yeah, exactly. That’s exactly it.

You couldn’t go with a weirdly heavy song at a time like that, after all.

(Yoshii) Right, you can’t. Instead of saying you can’t, I guess I’d say you have to go with “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo” during the times when you want to Baban-Baban-Baban.

Are the other band members happy when you put that song in the setlist?

(Yoshii) Hmm, I wonder (Laughs)

Like when you ‘re deciding on the setlist, and have to pick the second song during the encore, or whatever. Does it feel like it’s a given from everyone that it has to be this song?

(Yoshii) Yeah, I think so. Though I’ve never explicitly asked them.

Are you the one who primarily determines the setlists?

(Yoshii) No, we all decide together. When I put the song in, I ask “This is okay right?”, and they say “Yeah, why wouldn’t it be?”. But I’ve never asked them why they think it’s okay. (Laughs) Maybe I’ll ask them that next time! (Laughs)

Ask them “What about this song do you think is good?”

(Yoshii) (Laughs) I bet that will really surprise them! They’ll wonder why I’m asking them this all of a sudden. “What’s so good about this song? Why do we always save it till the end?” (Laughs)

Ha, that would be so weird.

(Yoshii) Yeah, it would be weird.

Anyway, there was just something about you all during this time period. Maybe there are some bitter sweet memories.

(Yoshii) Yeah, that’s probably it. There sure are. That’s why when we play songs from the first and second albums, it always really feels like an “I told you so”. Though we’re the only ones thinking about it that way! (Laughs) I’m not sure what the audience thinks about that.

4. Silk Scarf ni Boushi no Madam

Next is “Silk Scarf ni Boushi no Madam”, a song that you sung about your mother. Did you suddenly get struck with the idea to write a song about her, or was that something you’d been waiting to do for a long time?

(Yoshii) When I was writing this, I was just thinking of writing a simple song about a wharf woman.

Oh really?

(Yoshii) Yeah. At that point I was buying box sets of Shouwa-era pop songs.

Why? Do you like that kind of stuff?

(Yoshii) Yeah, I like it. I was just thinking about how we had a copy of “Hatoba Onna no Blues” (“Wharf Woman Blues” by Shinichi Mori) at home growing up, and how I wanted to listen to it again. I felt like it might be interesting to do a song about a wharf woman like you’d hear up through the 70s, but put a bit of a western spin on it.

Wow.

(Yoshii) I wrote that song just holding down an F chord like this. And I started coming up with the story as I was going through writing the lyrics, and I thought this one about Jaguar might be kind of interesting.

It feels like this song really stands out from the others on the album, since it’s self expression through fiction.

(Yoshii) Yeah, it even surprised me.

It’s a very emotional song, so it was very different from the other more unnatural feeling songs on the album.

(Yoshii) Because it was so much more refined? (Laughs)

Was it more refined?

(Yoshii) (Laughs) I tried to refine it more anyway.

Right, right. But since it’s a song that came from a concept, naked bodies came into the picture.

(Yoshii) Right.

Why do you think you didn’t write a song like this before then?

(Yoshii) Tweaking songs was a given a for me. I liked tweaking them, making them sound more unnatural and giving them a sort of artificial coloring. I was a big believer in it being rude to just send a song out into the world so easily, and I was always unhappy with the results.

So it wasn’t so much you entrusting your own mentality into some of your songs back then, so then in what way…

(Yoshii) It was interesting from an audio perspective.

Interesting in the same way that you’d say “Hey, look at this weird accessory”.

(Yoshii) Right. Like something you’d find in Daikanyama.

Despite that, did it sort of feel like lazily throwing a stone and saying “This is my soul crying out!”, but having people just be like “What the hell are you talking about”?

(Yoshii) …Yeah. It kind of just felt good to be done with it.

So it wasn’t like you were intentionally setting your emotions free, or redirecting them somewhere else or whatever.

(Yoshii) Right. I just thought of it as telling a story.

Ahh, so in short you thought about in terms of a single pattern in a methodology.

(Yoshii) Right, yeah. I hadn’t really told too many stories through songs up until that point.

You’d just tried to present individual scenes.

(Yoshii) Yeah. Sort of like you would with copy in a series of ads.

So then amidst your usage of the methodology of presenting weird ideas like in “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo”, you suddenly thought “Oh, it would be fun to just tell a story”.

(Yoshii) That’s exactly it.

And the first story you thought to tell had to do with you. Coincidences happen, but expression really can be a dreadful thing.

(Yoshii) It can be dreadful.

So the creative process you were building probably felt really amazing to you. You probably wondered just what it was you were even doing.

(Yoshii) Yeah. At first I did think “wow this is really cool”, but I never really was brought to tears by own self expression. Though it could sometimes be moving.

Well of course, you can’t really do that.

(Yoshii) Right, at least so far. I haven’t really had the necessarily elements to do it to yet. It’s like a ban on my own tears.

It is like that. Would you write something like a scene where your pet dies on a movie? Of course not.

(Yoshii) (Laughs)

It’s not so simple to make yourself cry like that. You were thinking “If I was someone else, this would move me”, but that always comes from the most unexpected places.

(Yoshii) Right. People say it’s strange, but I hadn’t really seen any well known movies up until then. There were so many: “Sunflower”, “Romeo and Juliet”, “Death in Venice”, etc. They won Academy Awards and everything, but I hadn’t seen any movies like that. I’d like seen more B-level movies, like ones directed by Andy Warhol, and horror movies and stuff. I finally starting watching more well known movies around our second album, so they may have influenced me.

Why hadn’t you watched any?

(Yoshii) I thought they didn’t have anything to do with me. I thought that they were all just boring. I thought they were all big long mental depictions that probably weren’t interesting at all.

This might be a different interpretation, but maybe you were subconsciously aware that it might be dangerous if you dove onto those mental aspects?

(Yoshii) Yeah, that was probably true.

I wonder if you didn’t realize that it was the weakness that you liked most about yourself.

(Yoshii) I was planning on getting rid of everything I’d taken seriously up until I turned 20. It’s a bit strange to put it so seriously, but things that were full of emotion were dead to me at that point. It might have been a matter of thinking “I’m not that kind of man anymore! I’ve already gone crazy, this is who I am now”.

But that seal obviously ended up getting broken.

(Yoshii) It probably happened with “Silk Scarf”. I probably said it before, but that song was really a turning point for me. A very big one.

I want to ask you about this since it’s a song about your mother. We’re talking about a lot of different things, because they’re important to you. But about breaking free from your mother…So even though you yourself say that you had a mother complex, you still ran away from home to escape the oppression you felt from her?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

Where did your desire to run away from home come from?

(Yoshii) Thinking back on it…of course my mother thought this too, but if my father had still been there, in a way he could have taken care of her. There was a part of me that wondered why I had to be the one to work and help out with things in my father’s place, so I left because I wanted to do the things I wanted to do. She was already against me playing in bands, and I was in a bunch of debt but didn’t really want to ask her to lend me money. But when I didn’t have the money to pay back the loan I took out to buy a bass at 23 and couldn’t get it from other women anymore, I called her up and asked her if I could borrow 20,000 yen. She said “You’ve got to be kidding me! Quit doing this already, just come back to Shizuoka and find a job!”. Then I said “Wait! I’ll pay you back 100 times that amount if you just give me three years!”. Then she said “Don’t be stupid!” and hang up on me! (Laughs)

What a shameful son you were! (Laughs) But you were fundamentally a very obedient and positive kid, so abiding by the rules that your mother laid out for you made for an honest life. So you had been running through life completely thinking that’s the way a person ought to life.

(Yoshii) That makes me sound like a train (Laughs)

But you eventually started doubting that way of thinking, right?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

But then you couldn’t take it anymore, and your body began rejecting it. And yet your head was still telling you it was the proper way to live. Needing to choose one or the other, you chose to listen to your body.

(Yoshii) Yeah.

It was your way of saying “I’m going to do what I want now!”. And when you did, well if you’re a logical person you’d be in “The correct choice is for me to choose how my own life is going to be, and not just live for my mother. In the end it will ultimately be good for her, and it’s the only choice I have so I’m going to do it” mode or “Forget it, I don’t need to live my life properly anymore. I don’t care if I turn into a bad guy, I want to live the way that feels good to me” mode. Which was it for you?

(Yoshii) The latter.

It was totally the latter one?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

So then it’s like you were calling your old self an idiot, saying that your new life was going to be decadent and you can do whatever you want. I see. “I can’t go back to living a respectable life, I’m goin’ all out!”

(Yoshii) (Laughs) It’s like I’m in a historical play or something.

So since you said that you turned into a bad guy, does that mean that somewhere within yourself you gave up on living life as a good person?

(Yoshii) Yeah. Back then I’d completely given up on it.

So then you’d definitely given up on the expression of a very positive world view through your own actions and encouraging people, which is something that would really come out later with songs like “Taiyou ga Moeteiru”.

(Yoshii) Yeah. I’d given up on that.

I see. I really get it now. So you were feeling weighed down by this during the first and second albums.

(Yoshii) (Laughs) That’s probably true.

So your positive outlook instead became one of being about writing more unnatural and odd songs, gaudy songs, or decadent and catchy songs.

(Yoshii) Yeah.

And that’s why “Silk Scarf ni Boushi no Madam” was about someone who had left their proper life behind them. It was something that had to happen.

(Yoshii) Yeah, it had to.

It must have felt really good to do that! (Laughs)

(Yoshii) That’s the first thing that came to me! (Laughs)

I see. And how did you feel about it being moving?

(Yoshii) To put it bluntly…it was a hassle, but on the other hand it also made me happy. It’s weird to say that it’s one of the most respectable song I’d written…but when I was working on the first and second albums, I came to think that I couldn’t continue on in this business by writing the same songs I had been before. I liked them, but I knew I couldn’t keep sending that kind of stuff out into the world anymore! (Laughs)

(Laughs) “The world is just too small for the beauty that I’ve created”

(Yoshii) Yeah. When I finished “Silk Scarf” I kind of felt like this was my last chance.

It felt like you had shifted gears.

(Yoshii) That’s right. Because that song acted as something of a shift change, I couldn’t really go backward to more unnatural lyrics. Yeah.

You went back to the way you naturally were.

(Yoshii) That’s right.

Did the other band members say anything to you when you finished this song? “Wow, your style really changed!”

(Yoshii) No, they didn’t say anything about it. Those guys never say anything about that! They do joke around about it sometimes. When I finish a song and show it to them, there’s like three seconds of silence. Then they say “Oh, this is good!” or something! (Laughs)

They’re the best partners you could possibly have!

(Yoshii) That’s true.

It really is. I thought this might have been a particularly difficult song to put together. Was it annoying to arrange for a band?

(Yoshii) I think the band arrangement for this song really came out well. When I was working on it, I thought it should be really basic. Then we just made some tweaks to it as a band.

That’s the power of composition.

(Yoshii) Maybe so.

And it’s all thanks to your mother, right?

(Yoshii) It’s all thanks to me! (Laughs)

5. Kanashiki Asian Boy

Next is Kanashiki Asian Boy.

(Yoshii) Right.

Jaguar, who appeared in the lyrics to “Silk Scarf ni Boushi no Madam”, was the main character of this album: Jaguar Hard Pain. It’s the story of this dead soldier Jaguar who’s spirit has journeyed 50 years into the future in search of his lover Mary. I think it’s pretty clear that Jaguar is meant to be your father and Mary your mother, in this particular concept.

(Yoshii) For starters, this was me still wanting to write my own version of “Ziggy Stardust”. It had nothing to do with “Silk Scarf”. I came up with the name “Jaguar” and realized “Ahh, that sounds kind of like Ziggy!”

(Laughs)

(Yoshii) There’s nothing that sounds like “Stardust” in the name, but I wanted to make it about the pain and suffering of this Jaguar. So I came up with “Hard Pain”. The album name became obvious, and I started writing the album. From there I came up with the fine details, like he was going to be a Japanese soldier. A Japanese soldier who was killed and and travelled to the future in search of Mary. I thought it was pretty cool, so I went with that.

What was the concept behind “Asian Boy” for example? Wanting to take another look at what makes Japan so great, or wanting to confront the typical Japanese aesthetic sense?

(Yoshii) Originally it had to do with the aspects of Japan that I liked. It wasn’t intentional, but I didn’t end up thinking much about main themes when writing it.

It’s really interesting to analyze this after the fact, but basically that natural disposition of yours that came out in “Silk Scarf” really wanted to come out again.

(Yoshii) It did come out again, didn’t it.

But at this point you still couldn’t sing something like “Taiyou ga Moeteiru”, with it’s messages of living life in a straightforward way and protecting your true self. This was something that felt real, but still with elements of a story to it. In a way your image was kind of a classical right-wing one, with foundations in freedom and peace, since rock ‘n’ roll is so about “love and peace”. But that love and peace didn’t come out in a very straightforward way for you, it came out through your shorter hair and military uniform…through changes like that. Because you fundamentally like that kind of stuff, right?

(Yoshii) I do.

I’m not talking about liking stuff like “I’ll die for my country!”, but liking the straightforward aspects of someone who feels that way.

(Yoshii) There’s a song on the album called “Red Light” where Jaguar sort of horribly deceives a woman and causes her grief. Is that what you’ve come here to do?!

(Laughs)

(Yoshii) When I think about it now, I’m not sure if it’s interesting or stupid: Putting out a song that explicitly says “I’ve come here explicitly to do this kind of horrible thing”. Even though a long time ago I would have said “Have you seen this kind of song before? It feels so good!” (Laughs)

I wonder. I mean it seems like the type of character a guy who put snails on himself or dressed in women’s clothing might adopt? Did you feel a sense of distance from your characters? Did it feel like you were actually performing?

(Yoshii) It ended up being that there was no Jaguar, it was just a character I was playing.

It was a performance, so it didn’t matter.

(Yoshii) Yeah. People said “You’re him” and “he’s you”, but I think my stance was always “No, I’m just playing a character here”.

The fact that it was just a performance gave you something of an indulgent excuse.

(Yoshii) You’re right. And that’s why my stage presence and MC style changed here.

That’s right. How would you say they changed exactly?

(Yoshii) I didn’t try to rile up the crowd at all anymore, or make them mad. Before I would sometimes make them angry and they’d boo at me. It may sound weird to say they booed at me, but it was because I would be sarcastic with them. But I didn’t back down even a single step from that, up until Jaguar.

Oh really?

(Yoshii) I was wearing shoes with big heels on them too, so I might not even have been able to move around very much (Laughs) It was the kind of staging I wanted to do at the time though. When I felt embarrassed by it I’d tell myself “No, I’m playing Jaguar”. So I’d run around singing “I love you, I want you” and stuff. Ahh, it was a lot of fun. That’s where the kinds of dances I do on stage now came from.

Ahh, I see. So all of that wasn’t confidence or anything like that.

(Yoshii) Not at all.

Wow, so you really were doing all of that unconsciously. And since you were doing it unconsciously, you were setting yourself free in sort of a half hearted way. Though you’d written a full album that kind of inherited the essence of the motifs that you explored in “Silk Scarf”.

(Yoshii) Yeah. And what was really interesting was that “Silk Scarf ni Boushi no Madam” and “Merry X’Mas” were on the same level as songs, to me.

I see. So I guess you didn’t understand “Silk Scarf” at all, at that point.

(Yoshii) (Laughs) I guess not! Even with “Second Cry”, I thought I’d finally gotten away from everything that came before. I’ve said that “Jaguar” was the beginning of a slump for me, and it actually really was. I call it a slump because I wasn’t able to make a heavy song like “Silk Scarf” for awhile afterward. And so the output from that were the songs on “Jaguar”. A slump is a slump, and I couldn’t write songs like those on the first and second albums, or “Bunched Birth” anymore. So whenever I’m at a loss for what to do next, I go to England. When we were recording “Sicks”, Heesey brought a copy of “Jaguar” along with him. I borrowed it, and it’s the first thing I listened to when we got to England. There’s a song on it called “Haruka na Sekai”, which had never really been that big of a song to me. But in re-listening to it I realized that it actually was quite a big song for me.

It’s a very emotional song, isn’t it?

(Yoshii) It’s a pretty painful song, I think. For me, “Haruka na Sekai” and “Merry X’Mas” are kind of…how to put it…

Added bonuses?

(Yoshii) You could call them bonuses, yeah.

They’re complementary.

(Yoshii) Yeah. That being the case, when I was listening to the album in England and the intro to “Merry X’Mas” started up after “Haruka na Sekai” had ended, I could really see Shuuji Yamaguchi’s involvement in the sound there. He was a sound engineer on the album. And to me it sounded like the “Jaguar Hard Pain” version of “Avant-Garde de Ikou yo”. It was like he was saying “That’s how I mixed it to be”.

Someone else managed to interpret exactly what you wanted yet again.

(Yoshii) Yeah, yeah! (Laughs) It really surprised the president of our management company, but I’m not too sure why.

I see. But that means it’s the real thing. You can’t do anything when you know it all. For example, the songs you wrote for the first and second albums: They have a unique aesthetic sense that The Yellow Monkey possesses as a band. And didn’t you say those songs feel really artificial? And you sort of wavered away from that for “Silk Scarf”. And wouldn’t you say that the album you made after doing that was more evolved than the first and second? Or at the very least say “It’s different”?

(Yoshii) Yeah, it’s definitely different. The third album is definitely different.

How do you feel that it’s different? Did it feel like to a certain extent, you had to tell the truth?

(Yoshii) …Yeah. Ultimately, that’s what it was. I was always finishing songs then looking at them and saying “No, this isn’t quite right. This is really cool, but there’s something more to be found here at the base”. And when the second album was done I felt more like “This isn’t something an adult would listen to”.

(Laughs)

(Yoshii) (Laughs) I thought that people with very narrow ranges would listen to it…because at the time, high school age fans of the group sent me fan letters. They’d say that all around them people listened to bands that charted higher, put out more refined music, and sold more. And when people asked them what bands they liked, they’d say “The Yellow Monkey”. And the person asking them would make fun of them by saying “Ahh, I’ve heard of them. They’re a band that’s like boiled eel served over rice (unajuu)”.

(Laughs) What does that even mean?!

(Yoshii) At first I thought “What do they mean by boiled eel over rice?!”, but I weirdly came to understand it. (Laughs) If you know The Yellow Monkey from the “Jaguar” era, we would have been kind of like boiled eel over rice to a kid who likes more refined music. If I try to put myself in the place of a kid who likes hamburgers or crepes, we would be like boiled eel over rice! (Laughs) But at the time it really shocked me! Yeah. It felt like I was being patronized.

To you it felt like “But I’m doing Shibuya-kei in the Minato Ward…”

(Yoshii) That’s a good one! (Laughs) But yeah, let’s see…I always wanted to read fan letters, and I still do. It’s the one thing I absolutely do regularly. I can’t just cast aside the people who take the time to write them. I don’t want to cast them aside. Both fans from before our major label debut and fans who have been listening to us since “Jaguar” send in letters. And I want to try to make albums that won’t disappoint those people…which has resulted in some sort of sense of responsibility for that springing up within me. And so strangely…since I did “Jaguar” and realized what kind of person I was, I started wondering “Ahh, I wonder if this will disappoint those kids if it ends up selling well”. Even though I don’t have to worry about that kind of thing anymore, I still weirdly do.

So did it feel like you’d been getting steadily more popular since “Jaguar”? Did it feel like support was spreading?

(Yoshii) I think so. More people had been coming out to the concerts. I got the impression that it was due to word of mouth once our live performances changed with “Jaguar”. I think the other members agreed with that too. That was the era where we were playing concerts all the time, including our first ones in halls. It eventually got the point where we still weren’t doing well in sales, but our concerts were always packed. We weren’t selling well, but we were playing the Budokan.

Yeah, yeah. So in a way, your stage presence for “Jaguar Hard Pain” opened communication channels with your audience for the first time.

(Yoshii) I’d say so, yeah.

How did you rank your changed style of performance? This seems like an excuse being made for you being the character Jaguar.

(Yoshii) Right.

You’re saying that it wasn’t actually you singing “I love you, I need you” like you said earlier.

(Yoshii) Yeah, at least half of it wasn’t me. The other half was Jaguar.

But singing it felt good?

(Yoshii) Right.

But to put it the other way around, it was a perfect fit.

(Yoshii) Everything down to the crew cut, right?

I guess you having wanted to show everything couldn’t really be helped. That you wanted to release your inner self. That you wanted to agitate others. It was always coming out from you in different forms: Spinning your wheels, putting snails on your face, dressing in women’s clothing, shaving your hair off…That was all you not understanding yourself.

(Yoshii) You said it well earlier, I should have been more honest and straightforward.

But this was being honest and straightforward for you at this point. To phrase it differently, you wanted to be even more straightforward than what straightforward was for you then. It’s like you were saying “I’m showing you everything down to my very guts, so show me yours! I won’t agree to this until you do!”.

(Yoshii) (Laughs) Right

You’re consistent, if nothing else. That’s why you couldn’t quite get a foot hold commercially!

(Yoshii) (Laughs)

6. Love Communication

Alright, next we go to “Smile”. And from that we have “Love Communication”. Were you happy that this one was a hit single?

(Yoshii) I was happy.

Maybe not so much with “Jaguar”, but when you compare this to the first and second albums, it seems like you wanted to start putting out more hit singles.

(Yoshii) When we were recording the demo tape for “Kanashiki Asian Boy”, all of us (including the director) were excited that it seemed like it could sell one million copies.

Ahh, so you’d planned on this happening earlier.

(Yoshii) “Planned” is a good way of putting it! (Laughs)

(Laughs) And when “Love Communication” was released, were you thinking that was going to sell one million copies too?

(Yoshii) Now that you put it that way, yeah. If I’m being honest, I was very pragmatic when writing that song.

I see. You can come up with this catchy of a song by being writing pragmatically?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

So then you weren’t being pragmatic with your writing up until this point.

(Yoshii) That’s why I’d always frustrate our director by saying things like “I could definitely write a song that would sell a ton if I wanted to! But if I do that, there’s no end to it all!”. When I think about that now, it was a pretty weird thing to say! (Laughs) But that’s how it was. If I wrote songs just so that they would sell…to me it meant that I’d be ignoring The Yellow Monkey’s masterpiece as a band that would come from making it big, and would allow for us to change Japan or leave our mark. But I said “I can write a song that sells if I need to”. They said “Then please do!”, and I was like “No, I don’t want to!”. I don’t know what the hell was going on! (Laughs)

You had confidence that you could do it.

(Yoshii) I did. Even now, I still do. It’s weird, even though things are different for me now than they were then.

I asked about this before, but “Smile” is a very strange album that to me, it seems very confused.

(Yoshii) Yeah. And I think I said before that I started figuring things out with “Smile”.

Ahh, I see.

(Yoshii) “Jaguar” was very raw, but I still couldn’t give up on wanting to do something that was more refined. So I posed it as a challenge to the sound engineer. But in the end people said “This isn’t really you, is it?”.

But you yourself thought that it was?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

To phrase it differently, your aesthetic sense was still your own, even though you were consciously writing this to be a hit single.

(Yoshii) Yeah. It was an album that welcomed in listeners that somehow understood all that. But the people who got into us through “Jaguar” already hated us because of this album. I’d get letters everyday that said “What the hell is this? You sold out, you assholes!”. Hearing that from people was inevitable, but at the same time I kind of felt like “Don’t decide what you think about the story when you came in right in the middle of the movie!” (Laughs)

But “Jaguar Hard Pain” sold some, so you didn’t think about doing more albums like that?

(Yoshii) Nope, there weren’t enough zeroes in its sales numbers. So our director and the president of our management company took us out to a cafe before we recorded “Nettaiya” and asked us what we were going to do for the next album.

(Laughs)

(Yoshii) They said “Selling 100,000 copies is fine for a band to sustain itself. But would you rather just be a band that sustains itself, or would your rather sell 1,000,000 copies?” Of course you’d say being a band that sustains itself and also sells 1,000,000 copies. Well we thought about it: Do we want to be a niche band that keeps on selling 100,000 copies, or do we want to go for it all since we’ve come this far? Everyone thought about it, and we decided to go for it.

That’s interesting. So you made a decision, and decided to go for it.

(Yoshii) That’s right.

Maybe you weren’t sure if getting results would be fun or futile at that point! (Laughs)

(Yoshii) Yeah. And that’s where I started realizing that rock can be difficult after all. It might be a weird thing to say, but that’s what I thought. But I don’t think of it in terms of “Well this album sold because I wrote more pop songs on it”. Not now, and not for “Smile” either.

I see.

(Yoshii) Yeah. It’s not just a simple of matter of an album selling because it was written with that kind of thought process.

And that’s why you were set free from the things keeping you down, in a way.

(Yoshii) Yeah, yeah.

You were thinking that you were being more pragmatic about your writing, but the truth is you were going all out with it.

(Yoshii) Yeah. But you know, “Love Communication” definitely…yeah it took a bit of time to write.

(Laughs)

(Yoshii) Maybe it wasn’t so much that, as it was that I was hesitant.

So you were aware of it at the time.

(Yoshii) Yeah.

But it’s totally okay, looking at it now.

(Yoshii) I guess so.

Now it’s like “What the hell was I even worried about?!” (Laughs)

(Yoshii) And that’s why it felt so good to play during the concerts in the “Yasei no Shoumei” tour for “Four Seasons”. I guess maybe it was a problem with my thought process or feelings at the time. Or my composition style or wording, or something.

So you thought that “Nettaiya” or “Love Communication” might have been you being calculating. But that actually wasn’t the case at all, structurally speaking. But it’s odd, because your current compositions are functionally different from these songs.

(Yoshii) Yeah. You know…this is a great interview (Laughs)

So then this did fairly well in terms of album sales.

(Yoshii) That’s true. It added a zero to the sales numbers.

And that ended up being a good thing.

(Yoshii) Yeah. Because we were treated differently after that.

Ahh, you mean by the public?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

Wow, it’s easy to understand why then.

7. Overture ~ Taiyou ga Moeteiru

In the time between “Smile” and “Four Seasons”, it seems like you managed to arrive where you are today.

(Yoshii) Yeah, and you know…I’ve been saying this a lot in interviews lately, but I feel like it was the last album of my slump.

Ahh, I see.

(Yoshii) Yeah. The last one in that slump that began around “Jaguar Hard Pain”.

So this album was written while you were still in your slump?

(Yoshii) Yeah. Because I messed around with the songs a lot. I was always saying “I can’t write, I can’t write”, and then writing the songs the day I was supposed to sing them for recording. I think of that as a slump. They didn’t just come right out of me. And the pop songs from this album were “Taiyou ga Moeteiru”, “Love Sauce”, and well, maybe “Father”.

You were worried about them.

(Yoshii) I was pretty worried.

And here you thought you had cast those worries aside.

(Yoshii) Half of me had! (Laughs)

But the other half of you didn’t feel like you had at all.

(Yoshii) It was like “This is all that’s left”.

Ahh, I see. Well first I’ll ask about “Taiyou ga Moeteiru”. This was the theme of our last interview (in Bridge Vol. 10), but basically you misunderstood yourself as being decadent and tried with all your might to make that into your character. But then that gradually changed. You love the morning and evening sun, you love deep emotion and easily being moved to tears, and you’re looking for a positive purpose in life. You gradually began to realize all of these things, right? And the desire to let all of that out manifested itself in “Taiyou ga Moeteiru”.

(Yoshii) That’s right.

Was this song written with conviction for all of that?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

You were thinking “Just let the sun keep on burning”.

(Yoshii) Yeah. But…how to put it…I legitimately thought this was an amazing masterpiece, but The Yellow Monkey’s capacity was expanding as a band. And I had a sense of impending crisis within me about it.

What kind of sense of impending crisis?

(Yoshii) I mentioned comparing every album to “Bunched Birth” before, but at the time I really thought that “Four Seasons” was going to surpass it. And, let’s see…that wasn’t really the case. It was a huge hit…but it just didn’t measure up in my mind. It was exciting to record, but this is more of a personal issue with me. Thinking about it now, it’s probably because of my attachment to “Tsuki no Uta” and stuff like that. I had actually wanted to make “Tsuki no Uta” a song about a man and a woman called “Shinju no Uta” (“Pearl Song”). That was the way I’d imagined it when I wrote it. But I was told to not release a song called that at this point. “Just what is this kind of vulgarity?! It might be a good song, but this isn’t really something an artist should be doing at this point in their career, is it?”. And you could say that I didn’t really like that at all, or it frustrated me quite a bit. So we fought about it before it was recorded.

Ahh, they wanted to be careful since “Smile” had strangely sold better than any album before it.

(Yoshii) Right. It wasn’t anyone’s fault, and I was the one who was in the wrong for pressing the issue so much. But the state of the band at that point was a really frustrating one.

But the big picture for you as a band was unclear. And if you ask me, you were growling like a monster in a kaiju movie.

(Yoshii) I see what you mean.

So you may have been afraid of something happening, but it’s not like you were thinking “It’s coming! It’s coming!”. You were irritated that things weren’t going as straight forwardly as you wanted them to.

(Yoshii) Right.

Ahh, I see. I said this during my interview with Heesey (in Bridge vol. 13), but you said something like “Are you guys going to be here when we do this next time?!” when you played the Budokan during this tour.

(Yoshii) Yeah.

And when I think about why that would be, it must be that frustration that was pent up inside of you. That’s why you had to say something like that.

(Yoshii) Yeah. And that’s why when making that album, that situation had to be hanging more and more above our heads. We wanted to sell more, so I was making lyrics easier to understand. That was the scheme we had laid out. I had to make them more refined or we were going to be in trouble. And in a way, this has all become reality now. But as an artist, going all out is really fun in a way. My stance up until “Four Seasons” was both “Ahh, for god sake” and “But we made a great album under these circumstances” at the same time.

I see. It sounds like it was a pretty difficult battle.

(Yoshii) As someone involved in it at all, yeah.

But the album did really well, even more so than what you seem to think of it.

(Yoshii) Right, right. That’s why listening to it several years after the fact, I feel like it’s probably just as amazing of an album as “Bunched Birth”.

To you “Four Seasons “and “Sicks” probably feel quite separate from each other, but maybe not as much to the listener?

(Yoshii) Yeah, I can understand that. I can definitely understand that.

It’s just that for you, there’s a huge gap in between them.

(Yoshii) Yeah. I mean if I was writing “Tactics” now, the lyrics would be different. But I guess that’s something I pretty much have to say. That’s just the way it turned out. But I pretty strongly feel that I don’t want to do things that way anymore.

But the fact that you wrote the lyrics to “Taiyou ga Moeteiru” is a really great thing.

(Yoshii) Yeah. I think “Taiyou ga Moeteiru” is a good song. There’s really no other way I could have written it. Yeah.

8. Father

And here we have “Father”, a song which also features some heavy themes in its own way. What made you think to write a song about the biggest trauma you’ve experienced in your life: The loss of your father?

(Yoshii) Well I was really happy about going to record the album in England. Yeah. I was so thrilled about recording there. And because of that, I was thinking about how grateful I was.

(Laughs)

(Yoshii) (Laughs) And I just kind of thought about my father. That made me think that maybe I should sing a song about him, since I’d found the resolve to. I wasn’t going to compare him to anything, just play it very straight. I guess I realized all of this myself in a really natural way, through going to England.

The story of your father is a pretty well known one to fans…but you lost your father when you were very young, and your father had been an actor at one point. He met with some setbacks, so in a way he passed without fulfilling his desires. That came together with your feelings toward him, and your feelings of loss after he passed.

(Yoshii) Yeah.

And you sort of touched on a version of it with the story of “Jaguar Hard Pain”. So did resolving yourself to deal with it here put some distance between you and all that, in a way?

(Yoshii) I’d say so.

Ahh, okay.

(Yoshii) Yeah. None of that was really necessary…though it might be odd to put it that way. I guess I wrote it when I thought about the fact that everyone in the world has a father. Of course I have my own feelings toward my father, but I knew that I also had my own style of rock that this fit into: Rock where I can sing about how everyone in the world has a father.

Ahh, I see.

(Yoshii) Right. I was able to sing that song pretty nicely once I figured this out. It doesn’t really have anything to do with my upbringing or anything like that, so I was able to sing it pretty easily.

So then it’s in the same context as “Taiyou ga Moeteiru”.

(Yoshii) Yeah, exactly. It’s the same with “Sora no Ao to Hontou no Kimochi”. I think this album is a masterpiece because of those three songs. At least that’s the way I feel! (Laughs)

I see. Basically singing about positive things in a positive way is often thought of as “not being very rock”, but to you it absolutely is.

(Yoshii) Right, right.

That’s the kind of theoretical framework that you came up with.

(Yoshii) For this album, yeah. And the response to “Silk Scarf ni Boushi no Madam” came about with this song too.

Ahh, yeah I really see what you’re saying.

(Yoshii) I’m able to pull it off pretty easily when I give myself the okay to do so. It’s like magic! (Laughs) Though I do tend to go astray.

It can get a little flabby! (Laughs)

(Yoshii) Yeah, exactly. Going overboard with the effector.

So did you feel a sense of accomplishment in writing this song and arriving at this point, even if you were worried about it?

(Yoshii) Yeah. Writing “Four Seasons”, “Taiyou ga Moeteiru”, “Father”, and “Sora no Ao to Hontou no Kimochi” really allowed me to get into “Sicks” mode. It made me think that I could do it because I was able to sing those songs. And since I could sing those, I could sing anything.

Basically since you wrote songs that were more straightforward, but…did you gradually build up the confidence to be able to sing a straightforward rock song about love for your father? Or did you just decide all at once to just do it?

(Yoshii) It was gradual.

When you were working on “Smile” for example, were those themes already set? Or did it feel more like you had to set them?

(Yoshii) Yeah, I guess you could say I set them…

They weren’t already there in your head?

(Yoshii) No. The seeds weren’t planted. I’d separate the things I like by nature from the unatural things. Sort of like a ladies comic or something.

You were all business.

(Yoshii) Yeah, exactly.

It’s also interesting that you didn’t really take a break in between the two albums. I see. So it feels like you’d made yet another shift within yourself during “Four Seasons”.

(Yoshii) That’s probably true, yeah. A shift…yeah.

After all, everyone around you was probably telling you to make “Smile Part 2”, right?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

You probably couldn’t write another album like that, at that point. You were asking yourself how you’d even make another album like it. But you probably knew that it was a necessary thing to do, right? You probably were in a slump because you were thinking of a direction to go in to achieve a soft landing or something, right?

(Yoshii) Right.

You couldn’t free yourself completely. But thinking about it now, you managed to free yourself even with “Smile”. Though you couldn’t think of it that way at the time.

(Yoshii) I get fired up whenever I’m writing something that hits close to home. I knew that things like “So I’m going to break it all apart” and “I actually like the sun, you idiot!” would get me the most fired up of all.

I see. The inside stories of Kazuya Yoshii are really interesting.

(Yoshii) (Laughs) I don’t know about that.

No, they really are interesting.

(Yoshii) I guess I wouldn’t know, since they’re stories about me.

9. Rakuen

And now we’ve finally arrived at “Sicks”. Did you know that this was going to be a completely different kind of album before you started writing it?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

Why was it able to be so different?

(Yoshii) Well…I think I mentioned it before, but first of all our situation had changed. “Jam” had sold quite well, and that may have created a sense of security. Though it’s weird to call it a sense of security. We were thinking “Ahh, it’ll all be fine!”, and that was the biggest reason. Though that seems quite obstinate.

So the success of “Jam” was a really big deal?

(Yoshii) “Jam” and “Spark” both, I hesitate to attribute it to just “Jam”. So at this point I was thinking that what I did on “Four Seasons” was still lacking. I said it earlier and I’ve thought so many times that I wanted to get myself fired up by just writing in a more straightforward way. And I think “Jam” is where I was finally able to do that. I didn’t necessarily have to write the line “A plane crashed overseas”, but that’s what I wanted to say. I think I get more fired up and my feelings improve when I say what I want to say. And I was finally able to do just that with “Jam”.

Do you think things would have been different if there had been no reaction whatsoever to “Jam”?

(Yoshii) If there hadn’t been any reaction, I think I would have put it all on the line again with the next single. But there’s no way I couldn’t have. Yeah.

Basically I thought you did what you wanted, and the results you got from “Jam” were directly connected to “Sicks”. And that seems to be true, but even moreso than that your real output came from your struggle within yourself during “Four Seasons”: Writing and performing songs, your perfect style, your exact feelings. Perfecting all of those things was huge.

(Yoshii) Yeah, that’s true. That’s why “Silk Scarf ni Boushi no Madam” and “Jam” are connected in my mind.

To express it in a bit of a strange way, “Silk Scarf” is unconsciously “Jam”.

(Yoshii) Right.

If it’s unconsciously “Jam”, then you’ve been conscious of something like “Jam” for quite some time.

(Yoshii) (Laughs) I’m such an idiot!

So at this point you’d started working on “Sicks”. Was a lot of the writing already finished?

(Yoshii) Yeah.

Did it all just kind of pour out of you?

(Yoshii) Yeah, it was the first time I had to lose my way in order to have fun.

It’s a really bad metaphor, but it’s the only one that comes to mind: It feels like a five year long bout of constipation finally cleared up! (Laughs)

(Yoshii) (Laughs) Switching to the Fun House record label acted as my enema! (Laughs)

(Laughs) Your style of performance and arrangement once again completely changed.

(Yoshii) They did.

The songs certainly must have been calling out to you.

(Yoshii) I certainly appreciate you putting it that way.

And you’d certainly gone through the trial and error of figuring out how you wanted people to hear certain songs up until this point.

(Yoshii) Yeah, yeah.

However you’d already decided how the songs on “Sicks” were going to sound, as you’d finished writing them. That sound was already there inside of you.

(Yoshii) It was. And the other band members were able to make it sound that exact same way. Yeah.

When you say “The song is telling me that it wants to sound this way” and the other members just hear it and understand…ahh, I just said something really good there.

(Yoshii) Yeah. That’s a music critic for you.