- ゴールをぶっ壊せ – 夢の向こう側までたどり着く技術

- Written by Hironobu Kageyama

- Released 01/10/2018

- Published by Chuokoron-Shinsha

Over 40 years after his debut as a singer, anime and tokusatsu song legend Hironobu Kageyama released a book detailing the ups and downs of his career from the very beginning, as well as thoughts on how other aspiring artists (or anyone aspiring to be anything, really) could learn from his own downs to help achieve their goals.

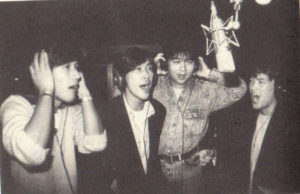

Kageyama started his career as a member of an all-boy pop group called LAZY in 1973. The original concept of LAZY was very different from what it turned out to be: Elementary school classmates Hironobu Kageyama (vocals, named “Michell” in LAZY), Akira Takasaki (guitar, named “Suzy” in LAZY), Hiroyuki Tanaka (bass, named “Funny” in LAZY), Munetaka Higuchi (drums, named “Davy” in LAZY), and Shinji Inoue (keyboards, named “Pocky” in LAZY) formed a rock band together named after the Deep Purple (one of their biggest influences) song “Lazy”. Their aim was always to be a rock band, but when they got signed to a record label, that’s just not how they were produced and marketed at all (they were told that bands like that weren’t selling at the time). They certainly enjoyed a period of popularity, but ultimately the direction wasn’t making any of them happy. They broke up in 1981, after the tour for their 7th studio album.

(“Akazukin chan goyoujin” (“Little Red Riding Hood, Beware”) was LAZY’s biggest hit. Side note – It was also covered by Kazuya Yoshii on his second cover album “Yoshii Kazbourne ~uragiri no machi~”)

From there, the members went off in their own directions: Kageyama started a solo career (more on that as we go along), Takasaki and Higuchi went on to form the heavy metal band Loudness (which even enjoyed popularity in the US), and Inoue went on to form a pop group with Tanaka called Neverland and later went on to run the anisong record label Lantis. Each of them certainly had their own challenges, but Kageyama probably most of all. His solo career didn’t exactly get off to a roaring start after leaving LAZY: He got some of the old fans coming out to see him, but ultimately people just didn’t seem to care that much. Just in order to keep being involved in music, he had to play shows for years without making any real money from them. He even heard through someone else that the president of his old record company from back when he was with LAZY said Kageyama was through in the music business. He just wasn’t cut out for it, and there’s nothing that he could do.

During that time he sustained himself mostly with a part time job of working construction during the day, and then music related work afterward. He would sometimes get recognized at his construction job by fans from his LAZY days, who would be kind enough to bring him drinks and such. However some of them couldn’t help but mention that it was a bit disenchanting to see someone who had been such a big star to them working just a normal job. He continued working this job part time way longer than you might think, before he was finally able to feel like he could make a living by working on music alone (which was always one of his biggest goals).

Around this time he also realized that he couldn’t get by as just a singer: He had to start writing his own lyrics and music too. He had no real idea where to begin though. Without any real methods for writing, his songs just kept turning into melody lines that he’d heard elsewhere at first. But little by little he started to get the hang of it, running his songs by members of his band and people at his record company. The best advice that he received during this low point in his career was to write songs that only you can write, and do things that only you can do. Kageyama also became a firm believer of not currying favor with fans. Of course he’s always grateful to them for their support, but they’re paying to come to see him. So the thing that they really want is for him to put on the best concert possible.

It would be a little while yet until the work that Kageyama was known for was actually written by him though. He became known for singing anime and tokusatsu songs, starting with the theme song to tokusatsu show “Dengeki Sentai Changeman” in 1985 under the alias “Kage”.

Why did he use an alias? At this time anime music wasn’t in the same state that it’s in now. There was no “anisong” phrase: Kageyama recalls them being called “manga no uta”, and they were absolutely looked down upon. Who would listen to them but the same children that were watching these shows, after all? Kageyama was being cautious, as he didn’t want the fact that he was performing an anime or tokusatsu song to potentially tank the rest of his career. However this song did well for him, and he got his foot in the door for getting offers to record other tokusatsu and anime theme songs as well, such as Saint Seiya’s “Saint Shinwa ~Soldier Dream~”

And while Kageyama has performed many hit anime and tokusatsu songs, the song he’s best known for is “CHA-LA HEAD-CHA-LA”. It was the first opening theme song for the anime Dragon Ball Z, released in 1989. And while he was recognized for his works before this, this song is what really got his name out and firmly set him on the path to being a staple of the anisong world. When Kageyama first got the offer to sing the song though, he had his doubts. The lyrics seemed a bit too weird, and he didn’t think the song would be very successful. Obviously he was completely wrong about at least one of those things! It wouldn’t be until the Internet age that he’d realize just how well this song would end up being known world-wide.

Kageyama also discusses how your typical anime song artist made money, all of which still apply to modern day. It’s not often that Japanese artists will discuss music business details, so this part was particularly interesting. Of course an artist gets royalties from CD sales, but it works a bit differently than you might expect. The royalties for just singing a song are significantly less than those for writing the lyrics and/or music to a song. For a new artist who is just performing a song, this may be only 1 percent of the cost of a the CD on each copy sold. This already makes it very easy to see why Kageyama realized that not only performing, but also writing lyrics and music was a good way to go if you’re trying to make your living as a musician in the anime song industry.

Sometimes instead of getting royalties though, you’ll be offered a buy-out contract. This means that the record company pays you a set amount for your recorded performance of the song. No matter how popular the single gets or how much it sells, you’ll get nothing additional apart from the amount you were paid up-front. Kageyama notes having some particularly frustrating memories of this in his own career. Apparently the most famous example of this though, is the theme song for “Oyoge! Taiyaki kun” (by Masato Shimon, 1976). It sold over 4,500,000 copies, and Shimon saw nothing more than what he was paid for the buy-out contract.

Performances at department stores and shopping malls have also always been another good way for anime song singers to make money, particularly if the show that the song is involved with gets popular. Kageyama recalls doing 2 to 3 of these performances a day, often in different locations, at the height of Dragon Ball Z’s popularity. Sometimes they also take the form of dinner shows at hotels as well. They’re always paid for by the company holding the event.

As anime music and Kageyama’s career entered the ’90s, he notes that a new trend quickly started taking root: Tie-ups. This refers to songs from already popular non-anime song artists, that have nothing to do with the anime in question, being used as theme songs. This still happens now, but it was a phenomenon that was extremely prevalent in the 90s. This of course all comes from the desire to have a song that will sell well right out of the gate, since it’s from an artist or band that people already love. This is just my own observation, but it seems like Rurouni Kenshin was the series that was the most successful with this idea, and really started popularity of this trend.

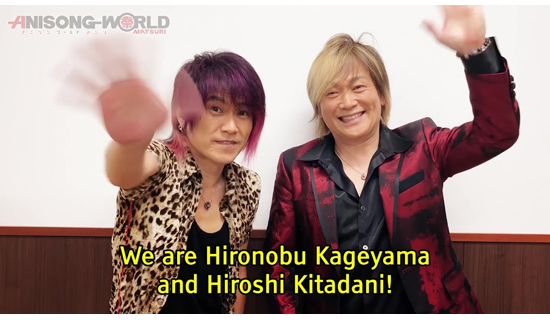

That’s why Kageyama formed anime song super group JAM Project in 2000. He still believed in the old way of doing things: Hand crafting songs for the anime that they’ll be used in. JAM Project could help anime song artists stick together, and not lose out to J-Pop groups. JAM started out as as Kageyama, Masaaki Endoh (GaoGaiGar), Eizo Sakamoto (Animetal), Rica Matsumoto (Pokemon), and Ichirou Mizuki (Mazinger Z, Gatchman, and a ton more. He was the eldest member of the group and an anime song legend, so JAM started out being based around him as the leader). Hiroshi Kitadani (One Piece) was added to the lineup in 2002, with Mizuki and Sakamoto departing shortly after (leaving Kageyama as the leader). Masami Okui (Revolutionary Girl Utena) and Yoshiki Fukuyama (Macross 7) were added to the lineup shortly afterward, in 2003. This remained JAM’s lineup until 2008, when Matsumoto left the group to focus on her own solo activities. They made the announcement of their debut as a group at a press conference on 07/17/2000, and since there wasn’t much attention on that type of anime music at the time, there were maybe 10 media people present to cover it.

(A very early JAM Project appearance on a how defunct music program called “Yoru mo Hippare”. It features an extremely rare instance of JAM Project as a group performing songs that were not released as JAM Project songs. It also features glam rock legend Rolly on guitar! Also stay for the whole video so you can see them performing “Ultra Soul” by B’z on another episode of the same program!)

Possibly because JAM was indeed a super group composed of stars of the anime music world all in their own rights, the group’s releases started out very strangely. Up until the 2001 single “Hagane no Messiah”, only some members sung on some songs. So you had titles like “kaze ni nare (featuring Rica Matsumoto and Hironobu Kageyama)”. It’s even noted that their dynamic was a bit weird on stage at first, just because they were all used to performing solo. They would find their footing fairly quickly though, and eventually turn into something of a one-stop-shop for writing and performing unique anime songs. Kageyama estimates that he himself writes about 70 percent of the material as leader of the group, but of course everyone contributes.

Over the years there have been a lot of requests for JAM Project to perform the individual members notable works as a group, particularly when it comes to performances outside of Japan. However that’s something Kageyama never really has wanted to do. It takes him back to his solo days just after leaving LAZY, where he was basically just getting by performing those past hits. He’s never wanted that same thing to happen to JAM Project, and it certainly hasn’t.

(One of my favorite Kageyama songs “Shine! Shinesman ~ You Are The Hero” for the tokusatsu parody anime “Tokumu Sentai Shinesman”.)

And that’s almost certainly one of the reasons why the members continue solo activities when they can, even being members of JAM Project. In 2003, Kageyama received a strange email in broken Japanese, asking him to come to Brazil to play at an anime event. He wouldn’t be paid for doing this, but he was asked to come anyway. He was very intrigued by this, so he actually decided to do it, along with a couple other of notable artists that had received the same invitation. As they got off the plane, there was a huge cheering crowd there. At first they thought that there must be some famous soccer player exiting the plane behind them or something, but soon realized that this crowd was actually for them.

And thus began Kageyama’s firsthand discovery about just how much people in other parts of the world wanted to hear the anime music that had been restricted to Japan for so long. The crowd that showed up to the event was enormous, and Kageyama was incredibly moved at how enthusiastic they were, and that they were all singing along to his songs in Japanese. He admits to himself that though he would have always said “people are people”, like most of us he had some pre-conceived stereotypes and notions about people outside of Japan just being different. These trips to perform all over the world helped him to legitimately get rid of those notions. Every time he’d return back to Japan and tell others how great it was performing in these other countries, no one would ever believe him until YouTube came about, and he was able to show them actual videos. Even today, Kageyama does his best to perform in as many different countries as he can, since it’s one of the more enriching experiences for him as a musician. From 2008’s “No Border” tour, he’s also been striving to do the same with JAM Project as well.

The later part of the book moves more from tales of Kageyama’s career, to him trying to convey the idea that no matter how difficult it seems, or how old you are, you should never really give up on your dreams. And these dreams should be very fluid things: If you manage to achieve one, there’s always something else beyond that to strive for. He tells one particularly moving story of being asked what he wanted to do for his 40th anniversary album. Not thinking that this was in any way achievable, he mentioned wanting David Foster (A Canadian musician, producer, and song writer), a longtime rock idol of his, to produce said album. It actually ended up happening, and Foster even convinced him to write a couple of songs in English for the first time. This dream of Kageyama’s ended up coming true at at over 50 years old, so it’s the best example he can think of for it never being too late.

(For those who have come for the video game stuff, here’s Kageyama and Maasaki Endoh performing the theme song for Rent a Hero (as featured in the game Fighters Megamix) with Sega’s own Takenobu Mitsuyoshi)

I admit that I came for the stories of Kageyama’s career, but ended up staying for the rest. I was a little weary with a title that sounded so self help-y as this. But the advice that Kageyama gives is very grounded and based on real life experiences of success, it doesn’t come from any sort of elevated or psychological perspective. And though much of the advice is tailored specifically at those looking to break in the world of anime music, it’s generally good for anyone striving to become anything. It reinforces one of the reasons I’ve always had a lot of respect for Kageyama: He’s very humble about everything that he’s accomplished. And even though he absolutely is, he doesn’t act like a rock star. I’d encourage anyone who can read Japanese and wants to learn more about him to check out this book (it’s not a terribly difficult read, anyone at an intermediate level could probably get through it), as well as his massive back catalog of songs for both his solo work and JAM Project.